Get up to speed on the parasites that can affect your horse this Spring!

Many types of parasites leave our equine friends vulnerable to attack, unfortunately leading to poor health and performance.

In warmer weather, these nasty parasites are more active, and so your worming strategy must be up to scratch to prevent illness in your horses.

To help you recognise, treat and prevent parasitic infections we have all the details on each of the most common equine invaders, so that you are in the know and ready to go this Spring!

Small Strongyles (Cyathostomins)

This group of parasites, known as “small red worms,” has over 40 species and are very prevalent. Horses on pasture can carry a burden of both large and small strongyles.

Strongyles Credit: Veterinary Parasitology at https://www.veterinaryparasitology.com/cyathostominae.html

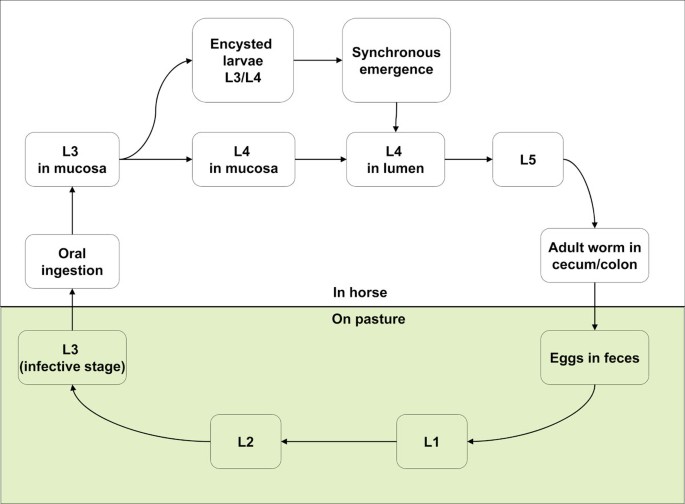

Parasite Lifecycle

- Strongyle eggs are deposited on pasture through manure and turn into larvae which the horse then eats.

Lifecycle of Cyathostomins. Credit: Equine cyathostomins: a review of biology, clinical significance and therapy | Parasites & Vectors | Full Text (biomedcentral.com)

- When larvae are ingested, they move to the large intestine and caecum. Here they burrow into the intestinal wall, forming cysts.

- There are two sources of infection during the grazing season. First, there are infective larvae developed in the previous grazing season and have survived over the winter on the pasture. Secondly, there are the eggs passed by horses though manure and nursing mares in the current grazing season.

- Larval levels in the pasture increase a lot during the summer months because environmental conditions are optimal for the eggs to develop to L3 (infective stage). This leads to high levels of infection in the Autumn.

- There is increasing evidence that many cyathostome L3 ingested during Autumn show some hypobiosis. Hypobiosis is a stage of parasite larval dormancy where nematode parasite larvae escape harsh environmental conditions by remaining in the wall of the intestine. These L3 stay in the large intestinal mucosa until the following Springtime when they emerge to cause severe clinical signs.

Clinical Signs

Cyathostomes (Nematoda, Cyathostominae) are parasites that can cause colic, decreased performance and growth, peripheral oedema (accumulation of fluid causing swelling), and diminished appetite.

When the cyathostome larvae encysted in the colon and cecal wall emerge simultaneously, this can cause larval cyathostominosis.

Larval cyathostominosis is characterised by protein‐depriving enteropathy, chronic diarrhoea, oedema, weight loss, colitis, and may be fatal (Traversa, 2008).

How to control Small Strongyles

- All animals on grazing over 2 months old should be treated with a broad spectrum anthelmintic every 4-8 weeks because horses of all ages are prone to infection from these parasites.

- A dosing regimen every 4-8 weeks will also help control other parasites.

- New animals joining a group should get an anthelmintic treatment. They should be isolated for 2 to 3 days before being introduced to the group after treatment.

- Ideally, a paddock rotation plan should be made so that nursing mares and their young do not graze the same area year after year.

- Overstocking paddocks is not recommended as this will increase the parasitic load.

- During winter, housed animals should be dosed with an anthelmintic effective against the larval cyasthostomes. This will lessen their risk of disease from mass emergence in the Spring.

- There is evidence that some species of cyathostomes are becoming resistant to benzimidazoles, such as pyrantel and piperazine. These compounds should be used strategically to avoid resistance. Alternating them with chemically unrelated anthelmintics such as the Macrocyclic Lactones (MLs) such as Ivermectin & Moxidectin on a yearly or 6-monthly basis is advisable. More details can be found here.

- Regular Faecal Egg Sampling is advised because it is a useful way of monitoring drug efficacy (Leveke et al., 2012).

- Pasture management may be helpful for some yards. Bi-weekly pasture cleaning such as sweeping or vacuuming or alternated grazing by ruminants may be beneficial.

Large Strongyles

Members of the Strongylus genus live in the horse’s or donkey’s large intestine. Their treatment and control are similar to that of small strongyles, as discussed above.

The three most common types of large strongyles that infect the horse are Strongylus vulgaris, Strongylus endentatus, and Strongylus equinus.

Large Strongyles. Credit Large Strongyles (bimectin.com)

Parasite Lifecycle

The larvae of large strongyles (red worms) like Stongylus vulgaris move through the body and will burrow into the arteries’ walls that supply blood to the small and large intestines.

This migration can result in blood clots, interrupting blood flow to the intestines and leaving scar tissue in affected arteries.

After about four months, the larvae move to the large intestine lumen, where they complete maturation.

Adults will lay thousands of eggs each day, completing the life cycle. The total life cycle takes six to seven months.

Large Strongly Lifecycle. Credit: LargeStrongyleCycle-L.jpg (800×810) (bimedaequine.co.uk)

The other two large strongyles (Strongylus endentatus and Strongylus equinus) have similar life cycles, but their larval migration is mostly through the liver. This migration results in damage to the liver.

S. endentatus and S. equinus larvae also go back to the large intestines to mature into adulthood. Their life cycle is approximately 6 to 8 months.

Clinical Signs

Anaemia, poor condition, poor performance, different degrees of colic, temporary lameness, intestinal stasis/ileus, intestinal rupture (though this is rare), leading to death.

Ascarids (Parascaris Equorum)

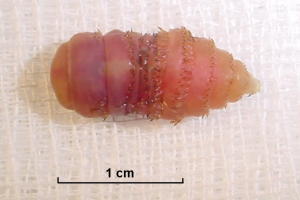

Ascarids, also known as roundworms, are stout, large and rigid whitish worms that can be up to 40cm long. These parasites primarily affect foals.

Horse Ascarids (Roundworms). Credit: Disease – Horse – Ascarids (bimectin.com)

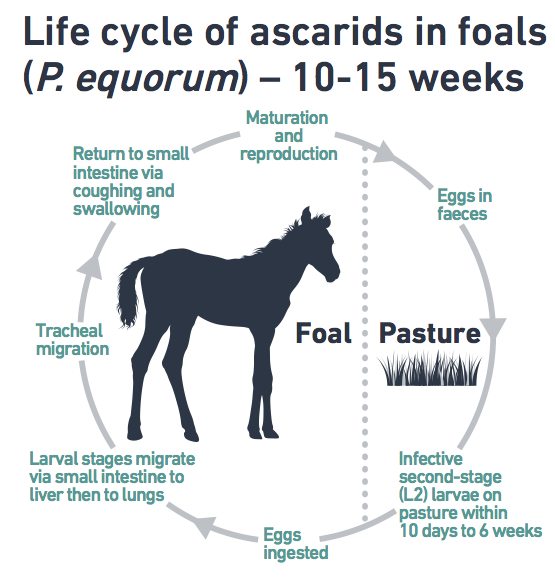

Lifecycle of the parasite

The lifecycle of ascarids is direct (meaning the parasite is transmitted directly from host to host without an intermediate (i.e., other species) host or vector).

Female adult worms produce eggs that are passed in faeces and can then reach the infective stage containing L2 larvae from 10-14 days. Sometimes low temperatures can delay this development.

After the horse ingests the larvae and they hatch, they will penetrate the intestinal wall, and within 2 days, they will have reached the liver.

In 2 weeks, they’ll have migrated to the lungs, where they will migrate up the bronchi and trachea. They are then are coughed up, swallowed again and go back to the small intestine.

The lifecycle of Ascarids. Credit: Foals – Part 2 – Farr & Pursey Equine (farrandpursey.com)

Clinical Signs

When the worms migrate (up to 4 weeks before infection), regular coughing and sometimes a grey nasal discharge may be visible. Some foals may appear unaffected and look bright and alert.

If the foal has a light infection, there may be no symptoms. For heavier burdens, the youngsters may experience ill-thrift, dull coats, poor growth, lack of energy.

Fever, colic and nervous disturbances, extreme coughing, enteritis causing bouts of constipation and foul-smelling diarrhoea are symptoms found in severe cases.

Diagnosis

Faecal egg testing, the presence of immature worms in the faeces.

Treatment & Control

Oral wormers with Benzimidazoles such as fenbendazole, oxfendazole, oxibendazole, or pyrantel, ivermectin or moxidectin prove to be effective against both the larval and adult stages.

Treat foals at 8 weeks and continue treatment as recommended by the wormer used.

Because the transmission is mostly from foals to other foals, it is recommended to avoid using the same paddock for mares and foals year after year.

Tapeworms (Anoplocephala perfoliata)

Many species of tapeworm are commonly found in equines. Tapeworms are different from other worms because they use an intermediate host; this is an organism that supports the immature or non-reproductive forms of parasites.

Tapeworm in the Intestine Credit: Worming – Towcester Veterinary Centre (towcester-vets.co.uk)

In the case of the tapeworm, it uses the forage mite (Oribatidae family) to complete its lifecycle.

Oribatid Mite. Credit: Ecology of Oribatid Mites | Ecological Sciences | Research | The James Hutton Institute

Tapeworm Lifecycle

The lifecycle of the Tapeworm. Credit: The Tapeworm Lifecycle – Equisal

Mature segments of the tapeworm are passed in the faeces, and the eggs are released, which then get eaten by the forage mite.

Once inside the mite, they develop in 2-4 months.

After the horse eats the mite (which is widespread on pasture), the tapeworm will be found a month or two months later in the horse’s intestine, where the cycle starts again.

Diagnosis

Faecal egg count, postmortem.

Clinical Signs

Sometimes horses do not display symptoms or may only show signs of failing to thrive or digestive upset. However, tapeworm infection can go unnoticed and then can develop into colic.

Treatment & Control

Wormers containing Pyrantel & Praziquantel are effective against tapeworm.

It is difficult to control tapeworm because forage mites are in herbage and pasture.

Keeping animals treated with wormers, particularly before they go on to a new pasture, is an effective way to control tapeworm infestation.

Bots (Gasterophilus)

Bots are obligate horses’ parasites, meaning they cannot complete their lifecycle without exploiting a suitable host.

The Bot is a fly and is 10-15mm in length, is dark in colour and covered in yellow hairs.

Bot Fly. Credit https://co0069yjui-flywheel.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Botfly.jpg

There are nine bots species, with six of these being of significance in horses, donkeys etc.

Three species of bots are most common to look out for in the horse, and all three lay eggs in different areas on the horse:

Gasterophilus intestinalis puts eggs on the forelegs and shoulders. G.haemorrhoidalis lays on the hair around the horses’ lips and G.nasalis – leaves eggs on the hairs of the jaw or throat area.

Parasite Lifecycle

There are slight differences in the lifecycle of different species, but as mentioned above, there are differences in the area where they lay the eggs on the horse.

All species buzz around the horse in early spring and lay eggs on different parts of the horse’s body, depending on the species. The following week, after the eggs are on the horse’s hair, they hatch into larvae.

Next, larvae get into the horse’s mouth. Larvae crawl into the mouth or are licked when the horse grooms itself.

Once inside the mouth, they will burrow into the horse’s tongue and the spaces between the teeth and gums, leading to necrosis or pus sockets in the gums.

After about 18-24 days, the larvae moult and move via the pharynx and oesophagus down to the stomach, where they attach to the stomach lining.

Larvae stay attached in the stomach for 10 to 12 months and detach, passing out in the faeces in the milder weather of Spring and Summer.

Once the eggs are in the faeces, they pupate, and after a month or two, the adult flies emerge to lay more eggs and start the lifecycle again.

Bot Lifecycle. Credit: https://www.equus.co.uk/blogs/community/the-bot-fly-101

Bot Eggs on Hairs. Credit: https://www.equus.co.uk/blogs/community/the-bot-fly-101

Bot Larvae. Credit: https://www.equimaxhorse.com/parasites

Clinical Signs & Symptoms

- Loss of appetite because of discomfort in the mouth

- Loose teeth

- Pus pockets in the mouth from burrowing larvae

- Inflammation of mouth and stomach

- Irritation of horse when the flies are buzzing around

Treatment and Control of Bots

Treat with broad-spectrum wormers such as Ivermectin and Moxidectin after a frost to kill adult flies in Autumn and then again in the Springtime to get rid of any larvae.

To control bots:

- Examine the coat for bot eggs regularly.

- Pay attention to areas around the face, such as the lips

- Remove eggs with a bot knife.

- If you find eggs in Summer and Autumn, sponge the horse with warm water containing an insecticide. The warmth from the water will stimulate hatching of the larvae, and the insecticide will kill them off.

Pinworms (Oxyuris Equi)

Pinworms are quite literally a pain in the bum for your horse. They cause inflammation, itching and discomfort around the tail area and make the horse sore and miserable.

Parasite Lifecycle

The lifecycle is direct. Adult worms are in the large intestine and caecum. When the females are fertilised, they move to the anus, where she can be seen popping out of the anus and laying her eggs in the perineal or perianal area in thick, yellowish-white gelatinous clumps. These clumps can contain up to 50,000 eggs!

When these eggs are ready to infect the environment (after about 5 days), they are rubbed off and contaminate the horse’s environment.

Other horses then ingest these eggs in bedding, feed or grass.

When the eggs are ingested, the larvae are released in the small intestine, migrate to the large intestine and then migrate to the caecum, where they develop within 10 days.

The larvae (L4) feed on the mucosa in the caecum, then mature to adults who then live in the lumen and eat the intestine contents until they are ready to reproduce.

It takes about 5 months for females to lay eggs after the horse first eats them.

The lifecycle of pinworms. Credit: Pony Club Victoria.

Signs and Symptoms of Pinworms

- Very itchy tail and rump

- Swishing the tail

- Broken hairs

- Bald patches

- The skin around the nail is inflamed or infected.

- The horse is unsettled and irritated.

- The coat is dull

- The horse may lose condition.

- You may see the adult worm or the eggs in the perineal area.

For a great example of eggs being laid in the horse’s anal area, take a look at this video.

Diagnosis

- Signs of pruritis (itching) in the anal area

- Signs of tail rubbing

- Finding the egg masses in the perineal or perianal area

- Evidence of the female worm in the faeces

Treatment & Control of Pinworms

Pinworms are susceptible to many broad-spectrum anthelmintics, and regular worming programmes can help to control them.

Effective anthelmintics for the treatment of pinworms include:

- Ivermectin

- Moxidectin

- Benzimadazoles (fenbendazole, oxfendazole, oxibendazole)

- Pyrantel

New horses should always be given a worm dose to avoid contamination.

If animals show evidence of infection, the perineal area needs to be cleaned about every 3 days using a disposable cloth to get rid of egg masses before they develop into larvae which can then be infective.

Stable hygiene is critical. Regular bedding changes are recommended. Feeding racks and utensils should not be in contact with the bedding.

If you have concerns relating to worm infestations in your horse or for veterinary advice, always contact your vet.

References

Strongylus Vulgaris – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

Veterinary Parasitology, 3rd Edition | Wiley

To read more of our horse care articles, visit our Welfare Tips and Information page here.

Author

Lauren Ross is a freelance animal health journalist, scientist & digital marketing specialist.

Cert Eq Sc, BSc Biovet, PgDip Livestock Health, PgDip Journ, PgBADM.

Leave a Reply